Basics for Radio Communication

| Site: | Open Flight School |

| Course: | Theory Basic Course |

| Book: | Basics for Radio Communication |

| Printed by: | Guest user |

| Date: | Wednesday, 4 February 2026, 3:19 PM |

1. Overview

Communication with other aircraft, as well as with ground stations, is of enormous importance when flying. This allows short-term procedures to be regulated and incidents to be prevented. But military cooperation between ground troops, control centres and aircraft would otherwise also be near impossible. Even cockpit-internal conversations often cannot be conducted without using technology due to mouse levels. In the past, all this had to be done by hand signals and / or light signals. Today, thanks to radio or wired systems, this problem no longer exists.

Smaller aircraft and helicopters are equipped internally with a communication system, which basically only connects all seats by cabling. Technically, this is essentially like a telephone and is called the Intercom. So everybody can talk to everybody and everybody can hear everything like in a conference call. Of course, this can also be prevented, so that only the copilot and pilot can say something and any passengers can only listen. Certain airplanes also have a connection for the intercom cable on the outside of the fuselage. This allows the ground crew to talk directly to the aircrew and to disconnect the connection just before the aircraft begins to taxi.

In addition there is actually at least one radio in every aircraft for external communication, but very often there are considerably more. By means of appropriate radio channels, on specific frequencies, the radiotelephony traffic can take place. This is done with the tower at the airfield, with the air safety (which controls larger parts of the airspace by radar) and / or with other airplanes. Communication takes place by voice, and English is the usual language for international air traffic.

The fact that you usually do not talk to your conversation partner about the last weekend or lunch in the canteen, but exchange important information, a few standard phrases are sufficient to achieve the basic aim. But even for this, abbreviations and unambiguous language methods have become established. They are unmistakable and can even be understood with an accent. Military pilots use many more abbreviations. They do this in order to exchange as much information as possible with as little language as possible. But more about that later.

In real life, everyone needs appropriate training and examination for transmitting. The so-called radiotelephony licence is available in different levels and is not so easy. Real pilots are obliged to pass the necessary level for the radiotelephony licence during the training. (more info)

2. Phonetic Alphabet

Since the invention of Morse messages, a uniform spelling alphabet has been used to avoid misunderstandings. A good pilot should know it by heart.

Application examples would be e.g. the naming of grid squares, taxiways, parking stands etc.

English Alphabet

| Alpha | Foxtrott | Kilo | Papa | Uniform | Zulu |

| Bravo | Golf | Lima | Quebec | Victor | |

| Charlie | Hotel | Mike | Romeo | Whisky | |

| Delta | India | November | Sierra | X-Ray | |

| Echo | Juliette | Oscar | Tango | Yankee |

English Numbers

The numbers are largely normal here as well. The 3 is spoken "Tree", since the English “Th” can be unclear over radio. Also, 4 is “Forwa”, 5 is “Fife” and 9 is spoken as “Niner”.

| 1 One | 2 Two | 3 Three (Tree) | 4 Four (Forwa) | 5 Five (Fife) |

| 6 Six | 7 Seven | 8 Eight | 9 Nine (Niner) | 10 One Zero |

Further information:

3. The Golden Rules

![By Szaaman [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.openflightschool.de/pluginfile.php/610/mod_book/chapter/288/640px-Gold_Ingots_on_white_background.jpg) Communication with other aircraft and control centers is extensive, extremely important and ultimately safety-relevant. Therefore, the radio is of importance.

Communication with other aircraft and control centers is extensive, extremely important and ultimately safety-relevant. Therefore, the radio is of importance.

Basically, the majority is not for you. it's like listening to the radio and occasionally contributing something to the program. 90% of all radio messages are intended for other participants. Their content is at best informative to follow the general situation in the airspace. However, it is the remaining 10% of the radio messages that affects yourself, that can not be ignored in the whole scope of communications.

There are three main things to keep in mind that make the whole thing easier for everyone involved:

- Radio Discipline: Transmit only you have been asked or you have something essential to say.

- Clearly defined messages: Who speaks to whom? What is it about? Short, concise, clear wording and information.

- Points of Reference: Essential in civil aviation and in military operations.

More in the following subchapters.

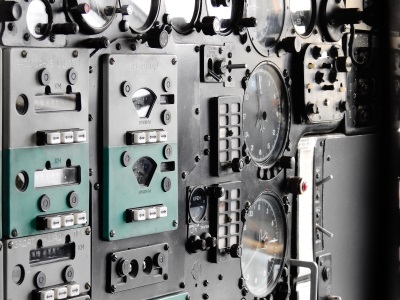

3.1. Radio Discipline

![Federal Archives, Photo 101I-695-0403-39 / Möller / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 DE (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)] , via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.openflightschool.de/pluginfile.php/610/mod_book/chapter/290/Bundesarchiv_Bild_101I-695-0403-39%2C_Warschauer_Aufstand%2C_Funker.jpg) In a radio communication the principle of radio discipline always applies. These are regulations about the behaviour when transmitting radio messages. The radio discipline includes: The prohibition of jokes, insults or intentional disturbances; such as playing music, unauthorized interruption, etc. These prohibitions exist mainly in the professional field of application. The reason for this is the maintenance of a minimum standard of orderly communication, their effectiveness and unambiguity (misunderstandings regarding the broadcaster, etc.) as well as the maintenance of security (priority levels such as Pan-pan and Mayday). In the latter case, occupied channels (frequencies) may, under certain circumstances, mean that urgent messages can not be received because routine radio broadcasts are taking place. The request "radio discipline!”

In a radio communication the principle of radio discipline always applies. These are regulations about the behaviour when transmitting radio messages. The radio discipline includes: The prohibition of jokes, insults or intentional disturbances; such as playing music, unauthorized interruption, etc. These prohibitions exist mainly in the professional field of application. The reason for this is the maintenance of a minimum standard of orderly communication, their effectiveness and unambiguity (misunderstandings regarding the broadcaster, etc.) as well as the maintenance of security (priority levels such as Pan-pan and Mayday). In the latter case, occupied channels (frequencies) may, under certain circumstances, mean that urgent messages can not be received because routine radio broadcasts are taking place. The request "radio discipline!”

Keep the radio quiet by:

- Only say what needs to be said.

- Do not speak when someone else is speaking. Exception: emergency messages. These, almost always, have priority and should be treated as such.

3.2. Message Structure

For a prospective pilot, it can be very difficult to find one's way through the murmur of radio messages and abbreviations. But basically it's quite simple. The radio traffic is actually nothing different than listening to the radio. When someone says your name, it's about you and your plane and it's your turn. However, aircraft registrations are used instead of names, such as D-4711EP. So everybody knows which plane is meant. And this is the first important lesson:

The first thing that is said in every radio message is always the recipient of the message. The sender is always named directly after that and then the content of the message comes.

Example:

"Tower, D-4711EP, request taxi to active." - The pilot of D-4711EP is addressing the tower and wants permission to taxi to the currently active runway.

"D-EP, Tower, clear taxi via taxiway A,B, D to hold south of runway 36." - The Tower allows the aircraft (which it responds to with the abbreviation of the registration) to taxi via taxiway A,B and D to stop south just before entering runway 36.

"Tower, D-EP, clear taxi via A,B,D to hold South for Runway 36." - The pilot and repeats the instruction to confirm that he has understood everything, and now also uses the abbreviation for his license plate number.

This sentence structure makes it much easier to filter out when you need to listen more closely, and you immediately hear who is talking to you. A second matter of course is that every instruction is repeated to confirm receipt of the message.

All this requires a lot of practice and routine. In the basic courses nobody expects it to work perfectly.

Private pilots have the advantage that they usually always have the same identification or call sign on their machine. In many aircraft there is also a sticker or sign with the registration of the aircraft in the middle of the cockpit. Airliners usually use the flight number, e.g. LH6325 (Lufthansa flight 6325). In the military sector, there are also names in the form of coded names, numbers, etc. that are defined in the briefing.

3.3. Reference Points and Relative Position Reporting

![By Saschaporsche [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia Commons](https://www.openflightschool.de/pluginfile.php/610/mod_book/chapter/287/640px-Navigation_Display_%28ND%29_on_Boeing_747-400.jpg) The best radio message is worth nothing if it is not clear to which position a direction refers.

The best radio message is worth nothing if it is not clear to which position a direction refers.

An example: Someone has lost his way and reports to the tower "I am left of the big city".

Actually quite simple, you think at first. Unfortunately it can be everywhere, because it is not known on which course the aircraft is flying. If he is flying south and has the city on the left, then he is more likely to be west of the city. Conversely, if he is flying north and has the city on his left, then he is east of the city. And besides it is not yet clear which city he actually means.

It is therefore very important for the receiver to know from which position the report of the direction is made.

Another example: A pilot reports that there are many enemy aircraft in the east.

Again supposedly precise and yet very inaccurate. First of all, who reported it and where are they? And even from there, east is a broad term: how far east?

As we see it is really important to communicate precisely where you are and in which direction applies to the report.

Next example: "Green Leader, Green 2, contact at 3 o'clock, high, close."

A Wingman reports a contact right above and close to his leader. This also sounds very precise at first, but requires that both fly the same course and not far away from each other, which will not always be the case even with well-rehearsed manoeuvres.

"Green Leader, Green 2, contact on your 3 o'clock, high, close." This is already really precise, but assumes that the wingmen can estimate accurately and estimates the position of the contact from the point of view of his flight leader.

To make a long story short, there is no panacea for this problem, at least not on a pure radio basis.

Modern fighter aircraft can locate enemies by radar and constantly exchange the positions of their own aircraft as well as those of recognized contacts by data link and keep them up to date. This allows every pilot to see at a glance what is going on around himself by using instruments and displays.

Bullseye

This is not possible with fighter planes from before 1980. Only precise radio communication and a known reference point adapted to the situation can help here. The so-called “Bullseye” reference point has proven to be a common procedure.

The Bullseye is a defined point of reference that only your own troops know. You could take any point on the map, e.g. a city name, but if the enemy hears the radio, he can interpret the position you are reporting. Therefore you take the neutral code name “Bullseye” even if the city is the point. Now the enemy has no idea where the “Bullseye” is or how to interpret the received radio messages.

All data refers to this one point. In a large area of application, however, this can become inaccurate with increasing distance from the bullseye, as the distance between angle divisions increases. Modern fighter planes can search with their radar and easily find a contact. Old aircraft without radar have to rely on the pilot's eyes. The less air space he has to search, the better. Here a good method is to have several clearly defined reference points in one area of operation and then to use the most adjacent one.

This topic will play an essential role in the practice of air combat in WWII as well as in Korea and even in modern warfare. It will therefore be expanded later in a further theoretical courses. For the moment we want to leave it at the above.

4. Aviation Jargon

![By Clark N S (Plt Off), Royal Air Force official photographer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.openflightschool.de/pluginfile.php/610/mod_book/chapter/283/544px-Lancaster_wireless_operator_WWII_IWM_CH_8790.jpg) Personal Callsign. In addition to the radio messages between pilot and tower or air traffic control, there is a special aviation language that has established itself independently of the phrases used with ATC (Air Traffic Control).

Personal Callsign. In addition to the radio messages between pilot and tower or air traffic control, there is a special aviation language that has established itself independently of the phrases used with ATC (Air Traffic Control).

It would be extremely impractical to use detailed radio messages in the middle of air combat. Usually there is only one or very few recipients of the message anyway. Usually only two airplanes or maximum 4 at the same time, at the same place, on the same frequency, are involved in the same fight. These must communicate very effectively with each other. This starts with the pilot personal callsign. The best known of these are: “Maverick”, “Jester”, “Viper” or “Goose”. All short two-syllable words. A long badly pronounced name as a callsign is a hindrance.

Brevity Code Words. For certain things and observations there are simple abbreviations called Brevity Code Words. The term “Angels 20” is faster and also unique. Alternatively one could say also "Level 20 thousand". "Fire spell" is nothing else like "I see Flak or other projectiles in the air". Or "Tally Ho!" is faster to say than "I engaging the enemy".

Many teams of virtual pilots go so far that they explicitly insist on this vocabulary. Nobody wants to hear "I'll shoot an infrared rocket on the left side of the target".

We would like to point this out here in the basic theory course, but do not make it mandatory in the respective aircraft courses. But especially in the WWII scenario it brings a lot of feeling into the simulation. With the more modern airplanes it is also desirable and usually easily connected with general English aircraft radio speech.

4.1. WWI Deutsch

Hier eine Auswahl der wichtigsten Begriffe der speziellen Fliegersprache in Deutsch aus dem 1. Weltkrieg.

| Begriff | Erklärung |

|---|---|

| Kiste | Flugzeug |

| Porzellan oder Eierkiste | Flugzeug nach einem Bruch |

| Briefbeschwerer | Fehlerhaftes Flugzeug |

| Grüne Frösche oder grüne Hunde | Flugzeuge bespannt mit grünlichem Stoff |

| Versuchskaninchen | Lernflugzeug |

| Trauerkloß | Lernflugzeug oft zu Bruch geflogen |

| Totengräber | Lernflugzeug, das den Tod des Fliegers verursacht |

| Eiserne Grüße | Bomben |

| Bauernschreck oder Zerberus (Grobian/Stammgast/Abonnent) | Häufiges Feindflugzeug |

| Mondsüchtige/Nachtwandler/der stille Herr | Abendaufklärer |

| Brummbär | Motor |

| Arbeitet im Akkord. | Motor der fehlerfrei läuft |

| Oller Bock | Motor mit Fehlern |

| Oller Bock, der ansschlägt | Motor mit Zündaussetzer |

| Hat einen Drehwurm oder fährt Karusell | Fehlerhafter Kompass |

| Kanone | Pilot mit großem Können |

| Luftchauffeur | Abfällig für schlechten Piloten |

| Küken oder grünes Gemüse | Flugschüler |

| Franz | Beobachter. Der Fliegerleutnant Blüthgen (Sohn des bekannten Dichters Viktor Blüthgen) soll Urheber dieses Namens sein. Sein kommandierender General fragte ihn bei einem Manöver, wie sein Beobachter heiße. Blüthgen soll da geantwortet haben: „Exzellenz, das weiß ich nicht, ich nenne ihn Franz". |

| Oberfranz | Tüchtiger Beobachter |

| Dauerfranz | Wenn er immer mit demselben Piloten fliegt |

| franzen | Beobachten |

| Er stanzt den Strich | Pilot hält den Kurs |

| Er verfranzt sich | Pilot verirrt sich |

| Affenfahrt | Erhöhte Geschwindigkeit durch Rückenwind |

| Redet mit Hochtouren | Pilot, der schnell spricht |

| Wird auf Touren gebracht | Pilot, der vom Vorgesetzten angegangen wird |

| Ha und Be (Hals und Beinbruch) | Wunsch beim Abflug |

| In der Waschküche | Flug bei dunstigem Wetter |

| Abschmieren | abstürzen |

| Bonbons, Knallerbsen, Nervenkitzler | Abwurfbomben |

| Saure Eier | Gasbomben |

| Fliegermäuschen | Handgranaten |

| Zahnstocher, Nägel | Fliegerpfeile |

| Gasblase | Luftschiff |

| Kreuzschmerzen | Ein Pilot, der noch kein eisernes Kreuz hat leidet daran. |

Fliegerjargon von 1914 -17

Quelle: digitale Landesbibliothek Österreich

4.2. WWII German

![By Devon S A (Flt Lt), Royal Air Force official photographer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.openflightschool.de/pluginfile.php/610/mod_book/chapter/284/464px-Lancaster_flight_engineer_WWII_IWM_CH_12289.jpg) Here is a selection of the most important terms of the brevity code words in German and their Allied equivalent. Pilots in the WWII have thus coordinated briefly and concisely with each other and with control centers. This is a small selection. There are a multiplicity of further terms (more than 200), but is too much for this course.

Here is a selection of the most important terms of the brevity code words in German and their Allied equivalent. Pilots in the WWII have thus coordinated briefly and concisely with each other and with control centers. This is a small selection. There are a multiplicity of further terms (more than 200), but is too much for this course.

General |

||

| Victor/Vitamins | Roger | understood |

| Ricardus | Say again | not understood/restored |

Flight Data |

||

| carousel | - | Course (e.g. "Caruso 185") |

| Haste | Buster | Own speed |

| Church tower | Angels | Height (e.g. church tower 5 = 500) |

| North Pole | - | above the clouds |

| Equator | Popeye | in the clouds |

| South Pole | - | under the clouds |

| Source | - | Current location |

| Rolf | Check Turn Right (Degrees) | Right (e.g. 3 x Rolf = 30 degrees right) |

| Lisa | Check Turn Left (Degrees) | Left (e.g. 3 x Lisa = 30 degrees left) |

| Carousel Rolf | - | Curve right |

| Great carousel about Rolf | Hook Right | 180 degree curve to right |

| Circus (above) | - | Collect (about) |

| waiting room | - | waiting loop, court round (large/small) |

| Garden fence | Home Plate | Own airfield |

| rocket | - | Start |

| Congo | Pancake | On the ground, landed |

| Luzi Anton | Pancake | landing, landing approach |

| Appear... Course xx | - | The shortest way... turn on course xx |

| Thirst, small, big | Chicken, Bingo | Fuel shortage, ending, critical |

Observations |

||

| I touch. | Tally | Visual destination contact |

| I'm blind. | No Joy | destination contact lost |

| Marketplace | - | Main target |

| sky blue | - | no enemy contacts |

Aircraft Observations |

||

| Question mark | Bogey | Unknown aircraft |

| Indians | Bandits | Enemy fighters |

| - on 12h | 12 O’clock | ahead |

| - high/low | - high/low | Height indication |

| mountains | Weeds | Low flying enemy fighters |

| Rolf Lisa make | - | waggle wings for recognition |

Air Combat |

||

| Timpani, timpani | Tally Ho | Attack |

| Ampulse | Tally Ho | Start Attack |

| Ampulle-Richardus | Press | Repeat Attack |

| xx IN or xx goes in | Xx IN | Manoeuvring to attack. |

| xx OUT or xx is out | Xx OUT or XX OFF | End attack. |

| Fire magic | - | Fighting, Flak |

| burglar | - | Entrance into anti-aircraft area |

| Emitted | - | under fire |

| I take over. | - | Stay focussed (on opponent), relieve someone |

| Long make, after... Rolf | - | Pull your opponent to the right |

4.3. Modern NATO Code Words

We will only deal with the most important terms here.

| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Affirm | Confirm / Agree |

| Negative | Negative / Disagree |

| Roger | Received radio message |

| Wilco | Will comply with orders |

| Say again | Repeat Transmission |

| Standby | Wait for more information / Pause transmission |

| Visual | Visual contact with friendly aircraft or ground forces; Opposite of "Blind" |

| Contact | Confirm sighting |

Further information:

- https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiservice_tactical_brevity_code

- "The Basics: Radio Comms 101" by "The Ops Center By Mike Solyom"

5. Basic Radio Calls

The subject of radio is a bugbear for most beginners, because they find the amount of different terms and radio calls overwhelming. In addition, there are some players who shy away from modern radio because they have had little to no previous exposure to English.

For these reasons we have decided to use only a few and partly shortened radio messages in the basic courses. In later courses, more phrases will be added, or the already known ones will be supplemented with further information. Therefore, you will only have to get used to the system for a short time and you will not have to learn everything again. We also accommodate our flight students with regard to the language. All phrases may also be spoken in German. However, every student pilot must at least understand the English phrases. But no further effort is necessary, because you learn them automatically because you hear them again and again.

It is important to share information. Even if the form and wording of a radio message does not correspond to the procedures, but the information itself is correct, that is still 100 times better than saying nothing at all!

Example:

"Kaltokri now taxiing to Kutaisi runway" contains all the important information. Of course "Kutaisi Airspace, Eagle-1, Taxiing to Runway 26" or "Kutaisi Traffic, Eagle-1, Taxiing to Rwy 26" is better.

But saying nothing and taxiing because you can't think of the right phrase is worse.

In the basic courses, there is no human air traffic controller (ATC) to interact with by radio. This greatly simplifies the radio process. In later courses, however, radio communication with human ATC is also practised.

Syntax

First, let's take a closer look at the components of a radio message.

Here is an example:

<Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, East Entry, 6,000 feet, to Land

<Kutaisi> Traffic

- This is the recipient to whom the message is addressed. (Who is called?).

Kutaisi is the name of the airfield. The angle brackets indicate that you may need to change the name of the aerodrome here.

- Traffic addresses all aircraft in kutaisi airspace. The word Traffic is used instead of Tower when no human ATC is available..

<Eagle-1>

- This is the sender of the message (Who am I?).

- This is your identifier which can be found in the mission briefing.

- For carrier operations, one speaks of Modex (number on the bow, e.g. 101).

- For land-based operations, it is the callsign (Roman 1-1, etc.).

- It does not necessarily have to match the in-game callsign (e.g. Enfield 1-1).

- If you have two numbers, the first is for the flight and the second is for your position in the flight.

- You also have to adapt this to the situation.

East Entry, 6,000 feet

- This is your location (Where am I?).

- The information consists of the position (absolute or relative position) and the height.

- Absolute position: There are certain fixed points in the approach charts, e.g. East Entry.

- Relative Position: For example 15 miles South of Kutaisi. So 15 miles south of Kutaisi.

- In the basic course we kept the use of the location to a minimum. Later you will use it more often.

- This is important for others to be able to assess where you are at the moment.

To Land

- This is the radio message (What do I want?).

- In this example, it is the announcement that you intend to land.

5.1. Departure Radio calls

We list here all the radio messages you need for the basic courses on take-off:

Cold and Dark on the Apron

- Description: You can start the systems, start the engines and establish taxiing readiness without the radio.

Ready to Taxi

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, Taxi to Runway <26> | Taxi to the Active

- Description: This is the announcement that you are now taxiing to the Hold before the runway.

At the Hold

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, Holding short Rwy <26>

- Description: This is the announcement that you are now at the Hold.

After checking that no one is approaching:

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, Lining up Runway <26>

- Description: This is the announcement that you are now taxiing onto the runway.

Departure

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, Airborne, departing to the South | Heading 180

- Description: This is the announcement that you have taken off and in which direction you are taking off.

Leaving the Circuit Pattern

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, Leaving frequency

- Description: When you leave the airspace of the airfield, you sign out.

5.2. Approach Radio Calls

We list here all the radio messages you need for the basic approach courses:

Arrival into the Airfield Airspace

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, 15 miles to the West, 6,000 feet, to Land | for Touch and Go | Into the traffic pattern

- Description:

- Before you enter the airfield airspace, you call and state your position and intention for landing.

When flying over a mandatory reporting point for approach:

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, North Entry, 3,000 feet | Initials Runway <26>

- Description: If you fly over a mandatory reporting point, send this message.

Firstly the entry point, then the initial point. This is indicated on the aerodrome‘s approach chart.

Or direct into the pattern or overhead break:

- English: <kutaisi> traffic, <eagle-1>, to join over head from the north 3.000 feet, to land | for touch and go | into the traffic pattern

- Description:

- If you want to enter the aerodrome circuit directly, you report this with the type of join and landing..

Downwind Approach

The standard is a left-hand pattern. I.e. all turns are flown to the left. Right-hand patterns are specifically indicated and then it is called "right downwind", "right base" etc.

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, [Right] Downwind Runway <26>

- Description: Message that you are Downwind.

Overhead Break

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, On the Break

- Description: Message that you are On the Break.

Final Approach

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, (Short) Final Runway <26>

- Description: Message that you are on Final Approach.

After Landing

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, Touchdown Rwy <26>

- Description: When you touch down, have braked and are sure you don't need to go around, report this radio call.

Then:

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, Runway Vacated

- Description: When you are off the runway, give this message so that others know the runway is available again.

For Touch and Go or Aborted Landing

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, (Touch and Go | Go Around) Runway <26>

- Description: If you do not intend to landing, but only a Touch and Go (i.e. touch down and immediate take-off), or a Go Around (Overshoot at 200ft), this radio message is next.

Parking

- English: <Kutaisi> Traffic, <Eagle-1>, <North Ramp>, (Shutting Down | For Rearming | Repair | etc.)

- Description: When you arrive at the apron, you call where you are and what you are doing there (one of; Shutdown | Rearm | Repair).